I’ll start with a confession; Sense and Sensibility is my least favorite Austen novel. I lay the blame solely at Marianne Dashwood’s feet. I find her behaviour and self-absorption more and more intolerable the older I get. It wasn’t always like this. When I was a teenager she was much more bearable. But not everything ages well, and I find that Marianne Dashwood falls into that category. Consequently, I approached The Dashwood Sisters’ Secrets of Love with a certain amount of ‘meh’.

I’ll start with a confession; Sense and Sensibility is my least favorite Austen novel. I lay the blame solely at Marianne Dashwood’s feet. I find her behaviour and self-absorption more and more intolerable the older I get. It wasn’t always like this. When I was a teenager she was much more bearable. But not everything ages well, and I find that Marianne Dashwood falls into that category. Consequently, I approached The Dashwood Sisters’ Secrets of Love with a certain amount of ‘meh’.

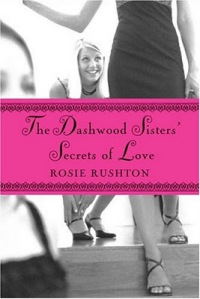

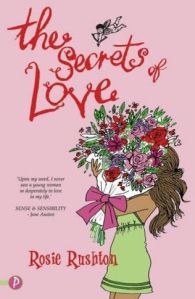

As an adaptation, “Secrets” stumbles in several places. But it gave me something to think about in terms of the marketing of Austen adaptations, not to mention the motivation behind writing one. The book is a UK import, and is actually the first in a series for young adults entitled Jane Austen in the 21st century (not to be confused with the “Darcy and Friends” series by Juliet Archer which uses the same umbrella title.) The author’s website introduces the book like this:

What would happen if you transferred the traumas of teenage love from Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility to the twenty-first century? How would Ellie, Abby and Georgie fare without the restraints of nineteenth-century England?

“How would the characters fare without the restraints of nineteenth-century England?” I found this question intriguing. I would love to know which restraints are meant. Decorum? Lack of an independent income? The ability to travel on one’s own? And if the Dashwood sisters are so constrained, what about Austen’s heroines in general? Perhaps the Bennet sisters at the mercy of the entail—but is it a unifying dynamic across the books? This was a nugget to revisit as I read.

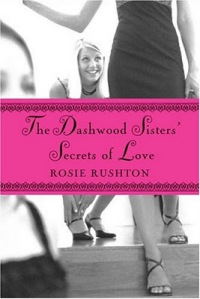

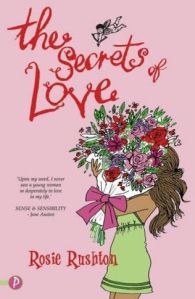

I was also interested by the differences between the American and UK editions.  The UK edition wears its Austen connection proudly, even going so far as to quote Sense and Sensibility on the front cover. The American edition makes absolutely no reference to the fact that it is an Austen adaptation with the exception of the title change. The addition of the words “Dashwood Sisters'” is a give-away to anyone familiar with Austen. It’s almost as if the title change was made to act as a secret code to knowledgeable readers: “Don’t tell anyone—but this book is really Sense and Sensibility!” But if the reader is a teen simply looking for some fluffy chick-lit, how would they know? It set me to thinking of just how loaded the words “Austen adaptation” are. In trying to determine if adaptations might encourage readers to pick up the originals, I had to also consider that readers might be turned off by a book grabbing on to a classic’s coat-tails. I also wondered why the rest of the series has not made it to our shores (book six is released this year in the UK.)

The UK edition wears its Austen connection proudly, even going so far as to quote Sense and Sensibility on the front cover. The American edition makes absolutely no reference to the fact that it is an Austen adaptation with the exception of the title change. The addition of the words “Dashwood Sisters'” is a give-away to anyone familiar with Austen. It’s almost as if the title change was made to act as a secret code to knowledgeable readers: “Don’t tell anyone—but this book is really Sense and Sensibility!” But if the reader is a teen simply looking for some fluffy chick-lit, how would they know? It set me to thinking of just how loaded the words “Austen adaptation” are. In trying to determine if adaptations might encourage readers to pick up the originals, I had to also consider that readers might be turned off by a book grabbing on to a classic’s coat-tails. I also wondered why the rest of the series has not made it to our shores (book six is released this year in the UK.)

So what of the book? It starts, funnily enough, with a Jane Austen quote:

“If a woman doubts as to whether she should accept a man or not, she certainly ought to refuse him. If she can hesitate as to Yes, she ought to say No, directly.”

If you know your Austen, you know that this quote is actually from Emma, not Sense and Sensibility. I found this choice irritating because it seems random. The quote is attributed to Jane Austen (as a “tried and true secret of love” to get things started,) but the textual source is not recognized. And in terms of the plot, it makes a tenuous connection at best. The quote on the front cover of the UK edition (“Upon my word, I never saw a young woman so desperately in love in my life!”) which is actually from Sense and Sensibility would have been a better choice. But no one asked me!

As in the original, there are three sisters: practical Ellie, drama-queen Abby, and tomboy Georgie. Their beloved father has remarried a predictably plastic younger woman (is there any other type of stepmother in chick-lit?) and moved out of Holly House, the ancestral Dashwood home in Brighton. When he dies of a heart attack, the three sisters and their mother discover that not only was he up to his eyeballs in debt, but that he put Holly House in the name of his new wife, and they must move to a tiny seaside village not nearly as hip as Brighton. Let the “traumas of teenage love” begin.

Someone very wise (okay, it was my mother) once made the observation that recent film adaptations of Austen novels are starting to bear more resemblance to the film adaptations which came before, rather than the books themselves. I often felt this way when reading this particular book. I felt as if I was reading an adaptation not of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, but of Emma Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility. No where is this more evident than in the character of Georgie Dashwood. As in Thompson’s film, the third sister is given a much more prominent role than she has in the original novel. I didn’t mind it so much in the film, because the heart of the story was still the bond between Elinor and Marianne. But in this book it was detrimental to the adaptation. Because Rushton was trying to divide the story between three girls, the relationship between the older sisters, in this case Ellie and Abby, was greatly diminished. Never mind lifting the restraints of nineteenth century England; Rushton completely lifted the dynamic between the two girls—a dynamic which saw them through some truly dark times in the original. As a reader of Sense and Sensibility I needed the counterbalance between Elinor and Marianne. I needed steady Elinor’s love to help me appreciate Marianne, just as I needed Marianne’s rants to help me endure Eleanor’s stoic heartbreak at the hands of Lucy Steele (and–let’s be honest–the spineless Edward Ferris.) Austen’s original working title was NOT Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret for a reason. Sense and Sensibility is a book about two conflicting personality types balanced by two sisters who love each other deeply. I would like to have seen more of that in “Secrets”.

Rushton did make some changes which, if I didn’t necessarily love them, I understood. Nick, the Colonel Brandon character, is simply another student at Abby’s school, who falls in love with her even though she is trying to set him up with her friend (Emma crosses over again!) Here is one instance where perhaps the plot is more about the restraints of the twenty-first century, rather than the nineteenth. There was simply no way to present a relationship between a 16-year-old school girl and a 35-year-old man as acceptable in a modern book for teenagers. The other noticeable plot change, which I did like very much, was the fact that Ellie finds out about the Lucy Steele equivalent (conveniently named ‘Lucy’ here as well) early in the story. And everyone else knows about Lucy, too, which leaves them all wondering just what Blake (aka Edward Ferris) is playing at. This brings a different dimension to the relationship, putting Blake in a position where he needs to actively and publicly chose Ellie. Like Marianne Dashwood, I find Edward Ferris less and less agreeable with age (not quite at the level of Edmund Bertram frustration–but getting there.) When Ellie sees Blake’s hesitancy, always finding an excuse to postpone breaking up with Lucy, her refusal of his affections is justified not in the name of sense, but of self-pride, an emotion which is much more accessible to a teen reader.

I also need to comment on all the brand-name dropping in this book. I found it to be a particularly self-conscious move in comparison to Austen, who wrote novels set during major historical events which she never even mentioned. Mentioning the brand of every different top Abby tries on might give her some fashion cred with modern readers, but excessive brand-name dropping tends to date books very quickly, and bearing in mind that this book was published in 2005, we are now talking about trends from 7 years ago. One of the reasons Austen’s themes seem so “timeless” is because they have center stage, not the Napoleonic War raging in the background.

Finally, it should be noted that Austen actually gets a mention in the text of the book, and it’s not particularly flattering. Abby is on a bus to King’s Lynn, which is taking much longer to reach than she expected:

“Not only did [the bus] stop in every village and hamlet, but every few minutes someone would stick out an arm, the driver would pull up and collect parcels and then yabber for ages about the weather or some woman’s bunions or the success of the village flower show. It was like finding yourself in the middle of a Jane Austen novel.”

Really? Well if that’s the case, no wonder the American publisher didn’t want to identify the book as an Austen adaptation. According to that description, Austen books are about pedantic backwater inhabitants absorbed with day-to-day trivialities. Funny—I thought Austen novels were about sparkling dialogue and witty, moral heroines who didn’t worry about the restraints of nineteenth-century England because they weren’t defined by them. That passage particularly offended because The Dashwood Sisters’ Secrets of Love was written by stealing all the good bits of an Austen novel while holding up Miss Bates as the poster child for Austenia. It’s hard to imagine that an author who adapts all six of Austen’s novels for modern teen readers isn’t a fan herself, but why would any author adapt books which can be summed up like that? Where’s the love?!

If an adaptation can spotlight the strengths of the original source, perhaps it is also true that an adaptation can highlight weaknesses. Despite its stylish (American) cover and the promise of secrets, which imply success, The Dashwood Sister’s Secrets of Love never rises above the level of lite-weight, because it focuses on the weakest part of the original book—the love stories. While no author is expected to improve upon Austen, innovative interpretation can successfully reimagine what Austen began (the recently published For Darkness Shows the Stars is a case in point.) By removing the meat of the original—the relationship between the eldest sisters, and the philosophizing about heart versus head–-Sense and Sensibility is reduced to just another book to read at the beach.

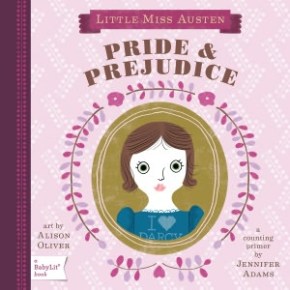

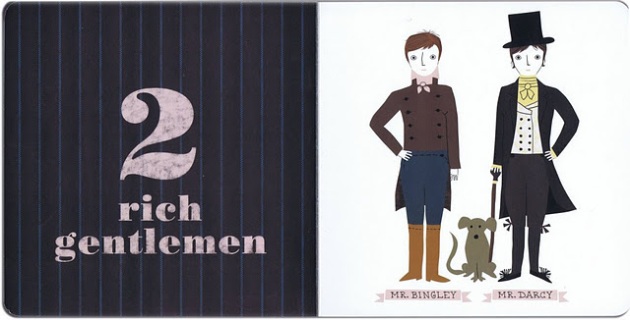

The Counting Primer presents us with “2 rich gentlemen”, conveniently identified as Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy. There is not much to differentiate between them, except maybe to guess that Darcy is slightly richer and slightly more formal because he wears a top hat.

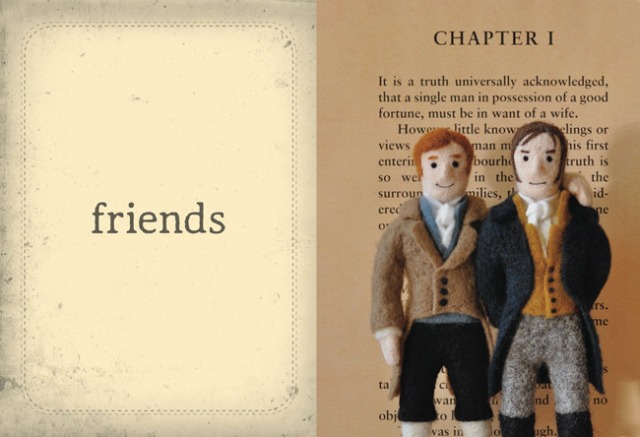

The Counting Primer presents us with “2 rich gentlemen”, conveniently identified as Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy. There is not much to differentiate between them, except maybe to guess that Darcy is slightly richer and slightly more formal because he wears a top hat. In the Cozy Classics, the very first word of the book is “friends.” There is no identification (in fact, not a single name is used throughout the book,) but the knowledgeable reader knows exactly who is who. (Also–managing to sneak in the famous first line–nice touch.) The choice of word and the conflicting personalities of the two men, so evident in the illustration, achieves a lot in setting the reader on the path of the story. This is further developed when the page is turned to reveal “sisters,” and Lizzie and Jane standing arm in arm. The reader understands that they, too, are friends, and that these two couples are the foundation upon which the book is built. Keeping strictly to a comparison as adaptations, point again goes to the Cozy Classics.

In the Cozy Classics, the very first word of the book is “friends.” There is no identification (in fact, not a single name is used throughout the book,) but the knowledgeable reader knows exactly who is who. (Also–managing to sneak in the famous first line–nice touch.) The choice of word and the conflicting personalities of the two men, so evident in the illustration, achieves a lot in setting the reader on the path of the story. This is further developed when the page is turned to reveal “sisters,” and Lizzie and Jane standing arm in arm. The reader understands that they, too, are friends, and that these two couples are the foundation upon which the book is built. Keeping strictly to a comparison as adaptations, point again goes to the Cozy Classics.